New study shows exactly how the manner in which mitochondria divide has remained the same since evolution began.

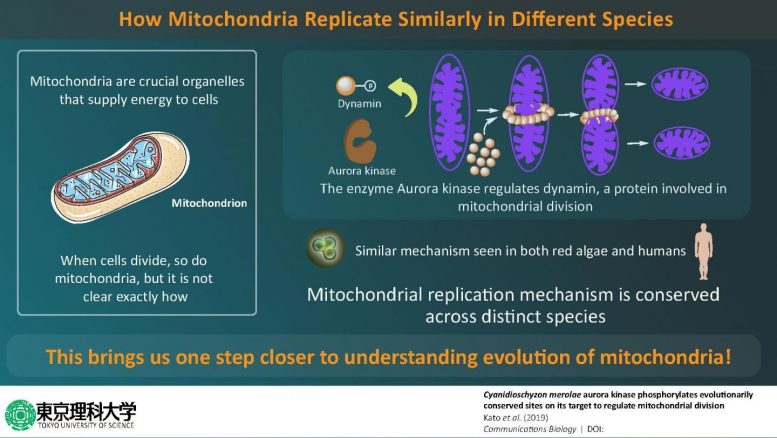

Cellular origin is well explained by the “endosymbiotic theory,” which famously states that higher organisms called “eukaryotes” have evolved from more primitive single-celled organisms called “prokaryotes.” This theory also explains that mitochondria—energy-producing factories of the cell—are actually derived from prokaryotic bacteria, as part of a process called “endosymbiosis.” Biologists believe that their common ancestry is why the structure of mitochondria is “conserved” in eukaryotes, meaning that it is very similar across different species—from the simplest to most complex organisms. Now, it is known that as cells divide, so do mitochondria, but exactly how mitochondrial division takes place remains a mystery. Is it possible that mitochondria across different multicellular organisms—owing to their shared ancestry—divide in an identical manner? Considering that mitochondria are involved in some of the most crucial processes in the cell, including the maintenance of cellular metabolism, finding the answer to exactly how they replicate could spur further advancements in cell biology research.

In a new study published in Communications Biology on December 20, 2019, a group of scientists at Tokyo University of Science, led by Prof Sachihiro Matsunaga, wanted to find answers related to the origin of mitochondrial division. For their research, Prof Matsunaga and his team chose to study a type of red alga—the simplest form of a eukaryote, containing only one mitochondrion. Specifically, they wanted to observe whether the machinery involved in mitochondrial replication is conserved across different species and, if so, why. Talking about the motivation for this study, Prof Matsunaga says, “Mitochondria are important to cellular processes, as they supply energy for vital activities. It is established that cell division is accompanied by mitochondrial division; however, many points regarding its molecular mechanism are unclear.”

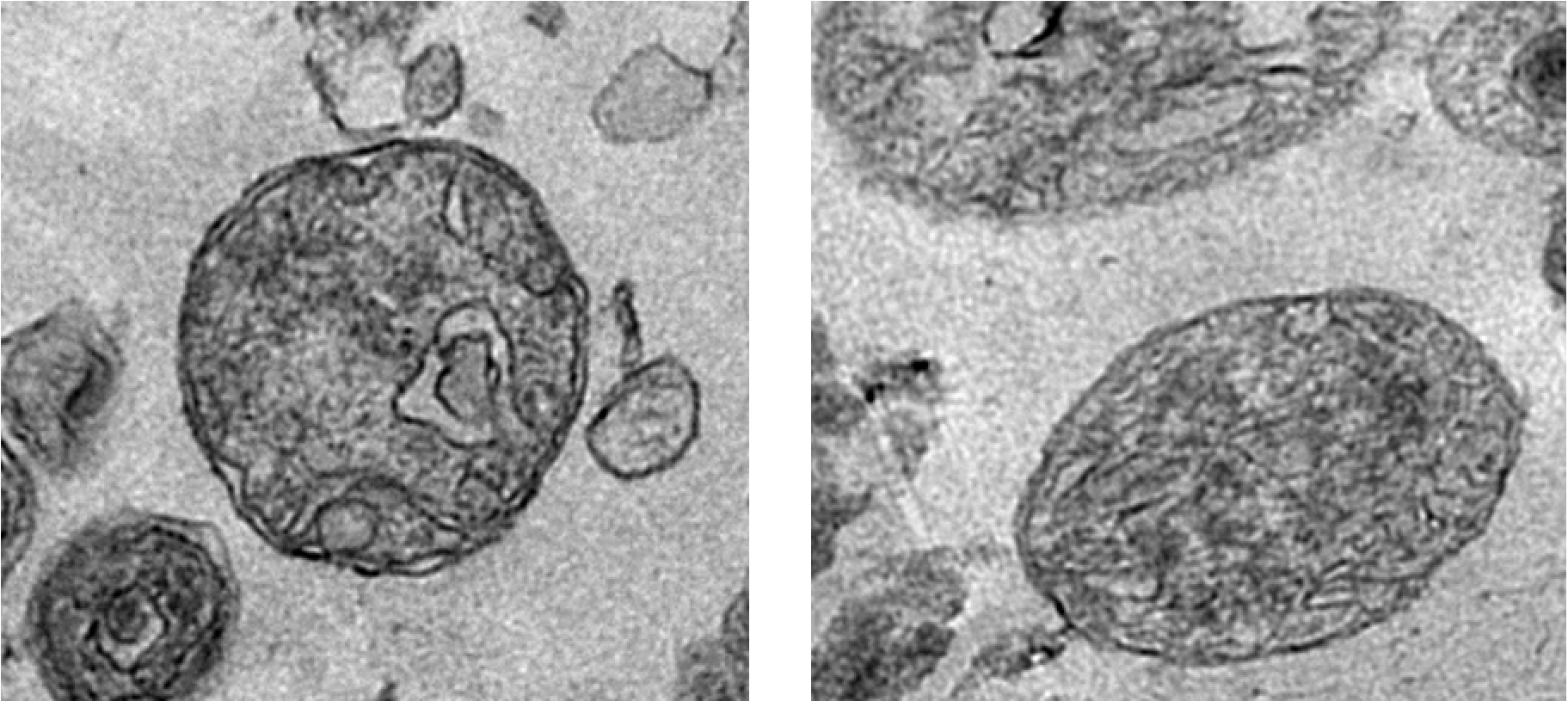

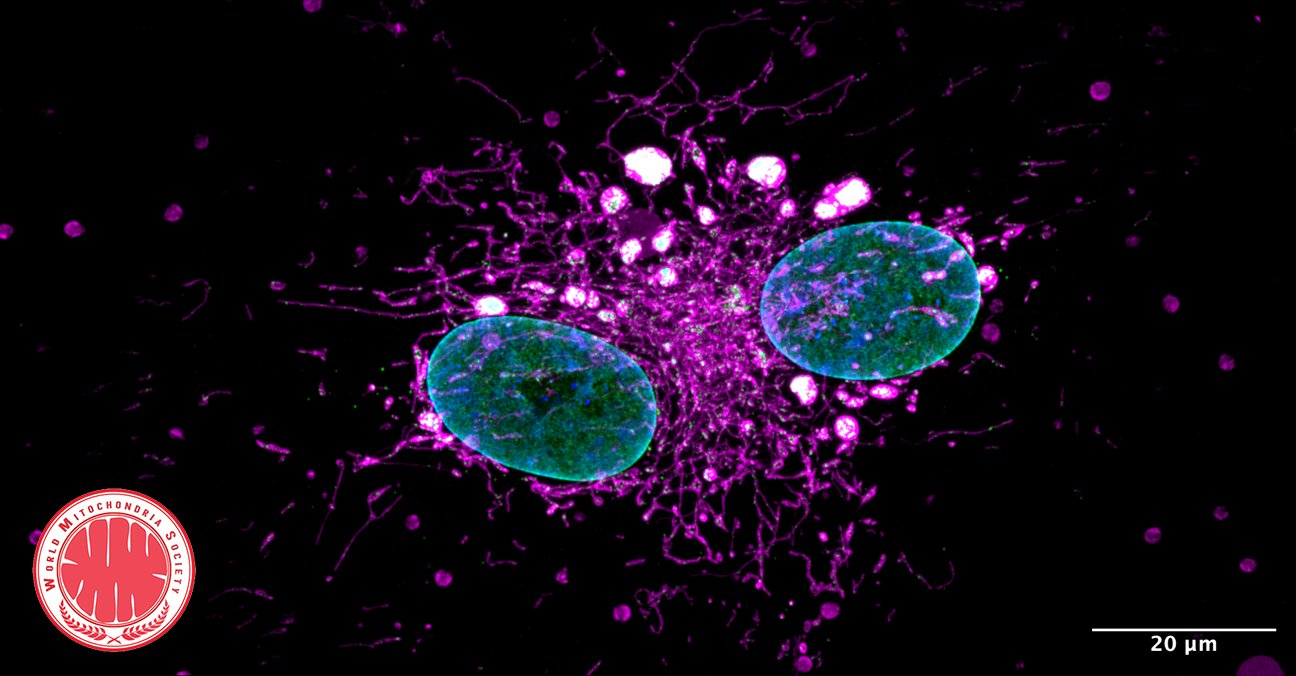

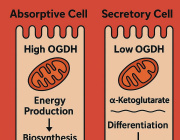

This exciting new research describes how mitochondrial replication is similar in the simplest to most complex organisms, shedding light on its origin. Credit: Tokyo University of Science

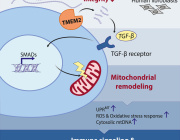

The scientists first focused on an enzyme called Aurora kinase, which is known to activate several proteins involved in cell division by “phosphorylating” them (a well-known process in which phosphate groups are added to proteins to regulate their functions). By using techniques such as immunoblotting and kinase assays, they showed that the Aurora kinase in red algae phosphorylates a protein called dynamin, which is involved in mitochondrial division. Excited about these findings, Prof Matsunaga and his team wanted to take their research to the next level by identifying the exact sites where Aurora kinase phosphorylates dynamin, and using mass spectrometric experiments, they succeeded in identifying four such sites. Prof Matsunaga says, “When we looked for proteins phosphorylated by Aurora kinase, we were surprised to find dynamin, a protein that constricts mitochondria and promotes mitochondrial division.”

Having gained a little more insight into how mitochondria divide in red algae, the scientists then wondered if the process could be similar in more evolved eukaryotes, such as humans. Prof Matsunaga and his team then used a human version of Aurora kinase to see if it phosphorylates human dynamin—and just as they predicted, it did. This led them to conclude that the process by which mitochondria replicate is very similar in different eukaryotic organisms. Prof Matsunaga elaborates on the findings by saying, “Using biochemical in vitro assays, we showed that Aurora kinase phosphorylates dynamin in human cells. In other words, it was found that the mechanism by which Aurora kinase phosphorylates dynamin in the mitochondrion is preserved from primitive algae to humans.”

Scientists have long pondered over the idea of mitochondrial division being conserved in eukaryotes. This study is the first to show not only the role of a new enzyme in mitochondrial replication but also that this process is similar in both algae and humans, hinting towards the fact that their common ancestry might have something to do with this. Prof Matsunaga concludes by talking about the potential implications of this study, “Since the mitochondrial fission system found in primitive algae may be preserved in all living organisms including humans, the development of this method can make it easier to manipulate cellular activities of various organisms, as and when required.”

As it turns out, we have much more in common with other species than we thought, and part of the evidence lies in our mitochondria!

Reference: “Cyanidioschyzon merolae aurora kinase phosphorylates evolutionarily conserved sites on its target to regulate mitochondrial division” by Shoichi Kato, Erika Okamura, Tomoko M. Matsunaga, Minami Nakayama, Yuki Kawanishi, Takako Ichinose, Atsuko H. Iwane, Takuya Sakamoto, Yuuta Imoto, Mio Ohnuma, Yuko Nomura, Hirofumi Nakagami, Haruko Kuroiwa, Tsuneyoshi Kuroiwa and Sachihiro Matsunaga, 20 December 2019, Communications Biology.

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-019-0714-x

News Source: https://scitechdaily.com